I just had one of those wonderful moments where a bunch of ideas that had been floating around in my head for a number of years came together and made sense, thanks to a section of Alva Noë’s book Out of Our Heads: Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons from the Biology of Consciousness. In Chapter 4, he challenges the common metaphor for the brain as the “Mission Control”  of the body — the place where all stimulation comes in and is noted, processed, and responded to. Instead, he says, our perception, and even our reaction, is distributed throughout our body and even through our environment.  To counter this, he offers the example of a snail’s response to being touched. At first touch, the snail will recoil, but with repeated touches, the snail becomes habituated to the touch, and doesn’t recoil. The sensory neurons in the snail’s nervous system are linked to the motor neurons, and the response to the initial touch is to cue the motor neurons to move the snail away.  As repeated touches occur, the snail’s nervous system learns the pattern as “normal” and the connection between the motor neurons and the sensory stimulus is lessened over time.  There’s no central brain managing this — the change is a result of the connection between the neurons and the patterns of action in the environment in which the snail is embedded, argues Noë. It’s not just about the changing in the coupling between the sensory neurons and the motor neurons, because that change would not occur without the repeated pattern of touch that the snail encounters.  It all happens without a “mission control” brain to process it.

This idea reminded me of an argument from Tor Nørretrander’s book The User Illusion. Nørretanders argues that we can’t possibly be conscious of all the information our sensory receptors can take in.  The amount of information that we can take in per second (which he derives by calculating the number of bits per neural receptor in our eyes, ears, skin, etc) is far greater than the amount of information that our consciousness can process (which he cites from psychological experiments). Instead, he argues, that all of the information we aren’t consciously aware of is exformation, and that brain filters out all of that exformation, summarizing the important details in the bits that make it to consciousness.  Most of what we sense, he argues, we deal with outside our consciousness.

Nørretranders’ argument has always been really interesting to me, and made a certain amount of sense, but I could never quite figure out what “outside our consciousness” meant.  Noë’s argument finally clarifies it for me. It’s not that we are not conscious of all that sensation, it’s that our consciousness is more than the deliberative process that Nørretranders is referring to as consciousness. Noë describes it this way:

“The real problem with the intellectualist picture [of consciousness]  is that it takes rational deliberation to be the most basic kind of cognitive operation when in fact thinking and deliberating themselves are the exercise of more basic capabilities for skillful expertise” (Noë, 2009, p.99)

What he’s getting at is that we’ve come to believe that there’s thinking and reasoning, and then there are skill-based things that rely on “muscle memory”, like playing the guitar or riding a bike. Â But here’s the kicker: Â thinking isn’t different from any other form of practice. It’s something we learn to do by habit, by doing it over and over again until we’re good at it. Â We practice it if we enjoy the rewards it offers, and we don’t practice it if we find it difficult or painful with no reward.

I don’t have a lot of physical talents. I can’t play a musical instrument, and I suck at most sports. Â I never even learned to ride a bike. Â Growing up, the rewards of physical activities never came as easily or as quickly as the rewards of practicing thinking. I get a thrill from seeing a pattern come together, and it’s not just a mental one, there’s a sense of physical well-being that I get when ideas snap into focus. Â It’s not always just mental patterns: I’ve had the same feeling when I could see a visual pattern fall into place, like a perfectly composed photo or a perfectly timed dance or movement routine. I’ve always wondered what gave other people that same feeling.

In recent years, I’ve developed an interest in women’s flat track roller derby. One of the things that interests me about it is comparing my perceptions of different skaters’ habits with their talk about the bout from their perspective.  Like any athletes, they’re not deliberatively aware of all the things they do, but they are definitely conscious of what’s going on around them. It’s clear from watching, then listening to skaters, that some of the decisions they make on the track actually go through their minds, but it’s never as deliberative as, for example,  “I’ve got to fake her out, make her block left, then pass on the right” until after the bout is over and they analyze their actions.  Many times, I’ve heard a skate watch  footage of herself and say, “Oh yeah, I was trying to…” (fill in the blank).  The “Oh, yeah” is the interesting part. It comes out as if she’s experiencing the moment for the first time, but it’s not that — it’s the first time she’s thought about the moment in an abstract, rather than an embodied, way.  What I’m arguing, and I think Noë would argue too, is that these two forms of experiencing the moment — being in it and reacting with muscle memory, and seeing it later and rationalizing the action — are both conscious experiences, but are reflections of one another.  It’s a way of understanding consciousness that I hadn’t picked up from Nørretranders, but makes his argument much clearer to me now.

In recent years, I’ve developed an interest in women’s flat track roller derby. One of the things that interests me about it is comparing my perceptions of different skaters’ habits with their talk about the bout from their perspective.  Like any athletes, they’re not deliberatively aware of all the things they do, but they are definitely conscious of what’s going on around them. It’s clear from watching, then listening to skaters, that some of the decisions they make on the track actually go through their minds, but it’s never as deliberative as, for example,  “I’ve got to fake her out, make her block left, then pass on the right” until after the bout is over and they analyze their actions.  Many times, I’ve heard a skate watch  footage of herself and say, “Oh yeah, I was trying to…” (fill in the blank).  The “Oh, yeah” is the interesting part. It comes out as if she’s experiencing the moment for the first time, but it’s not that — it’s the first time she’s thought about the moment in an abstract, rather than an embodied, way.  What I’m arguing, and I think Noë would argue too, is that these two forms of experiencing the moment — being in it and reacting with muscle memory, and seeing it later and rationalizing the action — are both conscious experiences, but are reflections of one another.  It’s a way of understanding consciousness that I hadn’t picked up from Nørretranders, but makes his argument much clearer to me now.

This makes much more sense of how we develop physical talents, for me. “Muscle memory” is a simple way of describing the neural and environmental associations that Noë describes in his illustration with the snail. It’s another take on Pavlovian association. We develop neural connections through physical repetition, and those connections are as much a part of our consciousness as the neural connections that we think of as reflection or memory.  They’re probably not even that different physiologically, except that they might reside in the neurons distributed throughout the body instead of just in the brain.

Interaction designers need to learn to use this, just as designers of any high-performance equipment do. Â Musical instruments are designed so that the controls are accessible and memorizable. Sports equipment is designed to be reliably graspable, and, like tools, allows players to extend their muscle power through the levers of rackets, clubs, gloves, and so forth. Â All of these things are designed to be learned by the body and used by it, with a fast transition from intellectual understanding to physical use. We don’t do this as well in interaction design, because we often get caught up in the intellectual meaning of what we’re designing. Â Perhaps we could let go of that from time to time, and think first about the physical actions people will perform when using what we make.

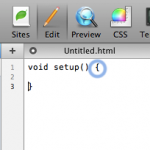

This doesn’t just have to apply to hardware design. Â Panic does this well in software design too. Like many code editors, their Coda programming editor highlights matching parentheses and brackets, but Coda does so with a pleasant ripple animation that catches your eye at first, and blends into the background eventually. It’s more noticeable than a static highlight, but not so noticeable that you focus on it. Â It works in the periphery. You’re conscious of it, but with the sensory part of your consciousness, not the deliberative part. Â You end up with a visual awareness of the edges of the block of code you’re working on that’s wider than where your attention may be.

This doesn’t just have to apply to hardware design. Â Panic does this well in software design too. Like many code editors, their Coda programming editor highlights matching parentheses and brackets, but Coda does so with a pleasant ripple animation that catches your eye at first, and blends into the background eventually. It’s more noticeable than a static highlight, but not so noticeable that you focus on it. Â It works in the periphery. You’re conscious of it, but with the sensory part of your consciousness, not the deliberative part. Â You end up with a visual awareness of the edges of the block of code you’re working on that’s wider than where your attention may be.

Lately, I’ve been working on a stool or standing up, because it’s easier for me to think while moving my body more. I haven’t seen any design outside furniture design that takes advantage of this for knowledge workers, but I’d like to. If you see any, please let me know.

Lately, I’ve been working on a stool or standing up, because it’s easier for me to think while moving my body more. I haven’t seen any design outside furniture design that takes advantage of this for knowledge workers, but I’d like to. If you see any, please let me know.

This was really great post and I related too. The snail example reminds of how the human body can adapt as well. For instance when we he an alarm go off it will startle us but if it continues to ring repeatedly than we adapt to it. Another part of the article I could relate to is when you talking about athlete when they about doing a move but don’t realize they were thinking, because this happens to me a lot. Great post

you might want to look at consciousness explained by daniel dennett

of course he doesn’t really explain consciousness but he has a pretty good go at identifying some fascinating experiments that highlight what it is…and giving a few analogies.